I feel that the moment you know you’re an artist is when you can comfortably sit in a room with yourself and just make. No peer over your shoulder coaxing or coaching you, no teacher commanding you through an exercise—just you in the room with Ego and Id, Superego if you’re lucky. Every sect of artist knows this moment. It’s pretty amazing, but no one is going to put you there but you. You’ve got to decide to get there.

I’d like to talk about the role decision-making has in my own art.

The breaking of the page

A lot of painters, drawers, and draftsmen are familiar with the fear of a blank page: taking the first mark and deciding where to go from there. It’s a cliff dive. I think it’s part of the reason people are so drawn to live performances of sumi-e, or ink drawings by the likes of Kim Jung Gi.. It’s admirable to watch someone go directly from the blank page to the finished product, with no in-between. I, too, love drawing directly onto blank pages with pitch-black ink, giving into the trust fall of this very specific type of "front-loaded" drawing, where you have to really think through to the final before any drawing takes place. It’s taxing on your mind, and deliciously productive if you can find the sweet spot. It’s like jazz—Art Tatum’s type. But Kim Jung Gi’s method does not always work for painting.

Painting, for most, requires sketching, for one, and studies for larger pieces. For years, I would avoid starting my painting commissions, dancing with procrastination until the last possible moment. Perplexingly, I was just as good at avoiding my tasks as I was at calculating the minimum required time to produce a decent piece. Push someone with ADHD into a corner, even if it’s self-designed, and we will suddenly become savants at many things—time management being the least of which. For me, I feel like as I’ve spent more time living with the “disorder,” I’ve realized that the solutions to executive dysfunction are not always the opposite of whatever behavior you’re suffering from; they’re usually a third (hidden) option. Being creative can sometimes unlock those options. Here’s an example:

Drawing on watercolor paper was always frustrating for me. See, watercolor paper, BFK, or any other thick paper designed to soak up delicious water-based paints (like the poster color I use) has something called “high tooth.” It’s all a fancy way to say the paper is thick. Technical drawing on high-tooth paper is challenging at best and infuriating at worst, but erasing on it is even more so. If you dare make a mistake on watercolor paper, you better pray you’ve got that pristine, untouched Tombow Mono eraser to whisper away the errors. For years, when I started getting serious about painting, I would bash my head (metaphorically) against walls, watching my erased mistakes reappear in uneven washes, gritty layers of graphite forever entombed in the paper, and, at worst, the tooth actually tearing in visible ways in the final product. But (cue the procrastination) I usually didn’t have time to redo a whole painting. Not to mention, I wasn’t that dedicated to perfection anyway. I’ve always been a lazier artist than your average Miyazaki or Frankenthaler. But I had to face facts. Drawing and erasing simply made my paintings worse. If I was to make great paintings, I would just have to create the perfect drawing the first time. At first, that’s the solution I thought would solve this frustrating dilemma.

But that wasn’t the solution. How could it be? After all, I knew sketching wasn’t wrong. To make mistakes is human! It may be the only thing we all have in common. Plus, the joy of sketching is actually the freedom to re-sketch, so long as you don’t get lost in the lockstep of indecision. I think indecision and decision regret are why so many folks have a relationship with drawing that can be summed up by this meme. But usually, re-sketching or refining a drawing produces a better result, as you analyze your mistakes or make something more accurate in general. Sacrificing this necessary step of artmaking would not produce a better end painting, and I knew that. I had to think of something else. Or I would never be a better painter.

Luckily for me, I have always been surrounded by those more talented and clever than me. Kenny Wroten, who makes the most psychologically engaging comics I’ve ever read, is an equally talented painter. Back in 2017, before they took the fateful journey to New York, where they still remain, they were kind enough to share a table with me in their studio in Kansas City’s West Bottoms, where we would work together for hours on our own paintings or projects, chatting about things we deeply cared about and forming the basis for a friendship that still grows to this day. One day, I saw them do something so simple that, at the time, I didn’t even think to apply it to my own clunky art process. They took a digital sketch they had printed and used transfer paper to copy it onto a piece of illustration board. Transfer paper! I can’t remember exactly when I started using this technique, because it certainly wasn’t the first time I saw Kenny do it. I didn’t run back to my studio at home and immediately apply it. That’s not usually how wisdom works—right away, at the exact time you need it. Anyway, some time down the road, probably when I was yet again frustrated with my own art process, I realized it was equally applicable to mine.

So, after a trip to Artists & Craftsman in Kansas City, buying enough transfer paper to last me through the next batch of commissions, I tried using this retro-fitted proxy instead of breaking the page directly. And, importantly, I didn’t do it exactly as I had seen Kenny do it—with a digital print turned carbon copy. At the time, I didn’t even have the tools to digitally sketch, not to mention I’ve always preferred pen or pencil on paper over digital. I mean, as a child I would spend hours drawing very complex things onto the back of lined paper, school assignments, or cheap printer paper I snatched from my parents' office. Maybe it was the casual nature of the printer or college-ruled paper that let me be free to experiment and explore. I’ve always been drawn to cheaper sketchbooks because the price of a Moleskine made ruining a page seem so wasteful that it wasn’t even worth buying. And then it hit me! Why not printer paper? Why not call it back to where it began, hyper-focused preteen, nose inches from the page, sitting next to my sister as we took shifts on the family computer?

So, since about 2020, I’ve used printer paper to sketch commissions and then transfer them to BFK using carbon paper. Because I’m free to refine or undo mistakes, even redo entire drawings on the printer paper, my BFK paper remains untattered by eraser friction and the ghost of graphite past. More interesting still, the printer drafts become unique souvenirs I get to keep of painting commissions that eventually get delivered, in full color glory, to clients.

Though the carbon copy practice is years old at this point, I still hold Kenny’s solution in great regard as a lesson for future studio problems. All the effort I would put off making the first mark on a piece of watercolor paper was not solved by making the first mark on a piece of watercolor paper. The way I solved frustrations with the blank page was not by making the page unblank, but by changing which page I was “un-blanking.” I don’t have to change my fear of ruining delicate BFK. In fact, the fear can live in harmony with the solution. It works like a charm and didn’t force me to just “get better at drawing.” It let me be free to make mistakes, which is really the key to getting better at art as a whole, drawing even more so.

Listening to the bacteria.

I mostly move based on an art philosophy that I picked up in college. It’s called “first idea, best idea.” You’re supposed to trust your gut’s creative intuition to tell you the idea that is best—key word, for you. I wish I could tell you who I learned it from, but I do know it arose around the time we learned about “thumbnailing,” a process where you take a prompt and create solutions about the size of a thumbnail for a final. If your prompt was “A cover of Vogue magazine for the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,” your thumbnails would show the TMNT in a variety of poses, draped in luxurious fabrics or fashions. The “first idea, best idea” of that prompt would literally be the first thing you think of when given it. You, reading this, have a first idea, best idea of that prompt. I’m curious what you, specifically, think a cover of Vogue magazine for the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles would look like. Leave a comment if you want. :)

All that said, I believe the more you can take a first idea and run with it to completion, the more you’re telling your gut creative intuition, “You’re right, I hear you!” When I am asked to solve prompts, or approached by freelance clients with specific requests in mind, I usually give them four to five options. But secretly, I hope they choose the first idea, because usually that’s the one my gut wants to produce the most. Another general rule of thumb (ha) for thumbnailing is: NEVER SHOW A CLIENT A SKETCH YOU’RE NOT WILLING TO TAKE TO THE FINAL ART, BECAUSE THEY WILL ALWAYS CHOOSE IT. I don’t make these rules, but I have seen them in action. If you don’t like the sketch, don’t show it to them. The client’s tastes can’t always be trusted. Trust me.

Despite its reliability in my own practice, “first idea, best idea” has its limits. If your gut is an unreliable narrator, overly anxious, or likes to rethink most decisions before pencil ever touches paper, or tends to point you toward the same ideas or options over and over, it may be time to redefine your gut.

Gut flora influence almost every aspect of our lives. Balance your gut, and you may just see that your ability to decide improves. If your body’s overall flow is better, if its physical inputs and outputs are regular—stay with me here—your mind, and by the transitive property, your creative process, will be too. There are others more qualified to talk about this than I am, so I can only offer my anecdotal testimony about the changes I’ve made over the last 8 years and how they’ve bettered my mental health, hormones, and overall happiness. Time-restricted eating, eating more fiber and greens, as well as only drinking caffeine between the time I wake up and noon, have all really benefited my overall health, which has made me a better person and artist. The legend of the starving artist is equal parts myth, poverty, and eating disorder.

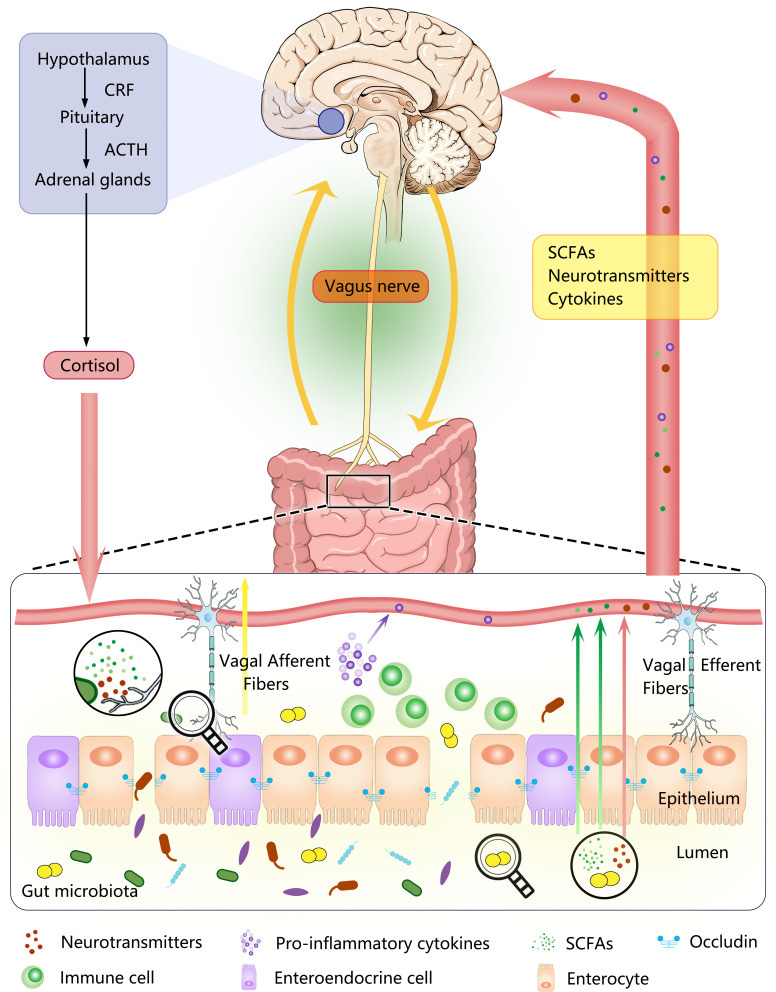

I have a dear friend, Jonah, who likes to talk about how humans are just a bunch of “bacteria in a trench coat,” and some days, with how much my mood and mind depend on something as simple as a tummy ache, I believe it. Science has shown that the gut-brain connection is super strong. The vagus nerve, the longest and most widely distributed brain nerve, stretches all the way from your noggin to your intestine. So, when you can’t distinguish whether you feel nervous in your head or in your belly, that’s why. But the “gut” isn’t just a muscle...

At 4 trillion microbes, with more than 1000 species, it is not surprising that 99% of the human genetic composition comes from the genetic material carried by the intestinal microbiota

For my plain language hungry brain, it’s a reciprocal ping-pong game of…

Brain: “I feel this way”

Gut: “Well, I feel this way becase you feel that way. Also— I ate mcdonalds earlier so it’s already an emotional wasteland in here.”

Brain: “Oh, well I feel this way because you feel that way about me feeling the first way. AND I really feel a certain way about the mcdonalds, too, so thanks.”

Gut: “OH THAT’S RICH COMING FROM YOU-”

And so on. It feels like any conversation in the comments online right now. In a dysfunctional system, nobody is listening and everyone is reacting.

This is why it’s simultaneously so annoying and so accurate when people recommend things like meditation, mindfulness, and exercise to people suffering from mental blocks or severe mental health issues. Anything that can break up that negative neurochemical feedback loop of the gut-brain connection—via a flush of our brain’s transmitters or healing our gut’s delicate cilia—can potentially unlock a new balance. And with new balances (ha) come new confidence. If your gut and brain really agree, you may even reach moments of “flow.” And flow-state decisions, for me, feel like they just pour out of you. Picture Shohei Ohtani hitting a home run after pitching a perfect inning, or, for those of you cultured types, Marina Abramović staring into people’s souls for four hours straight. “Flow” can shortcut the distance between decision and action. You recognize a need and fulfill it with the “first idea, best idea.” I think that principle (FIBI) is both the key to flow, and, in the long term, after holistic conditioning, the gut-brain connection.

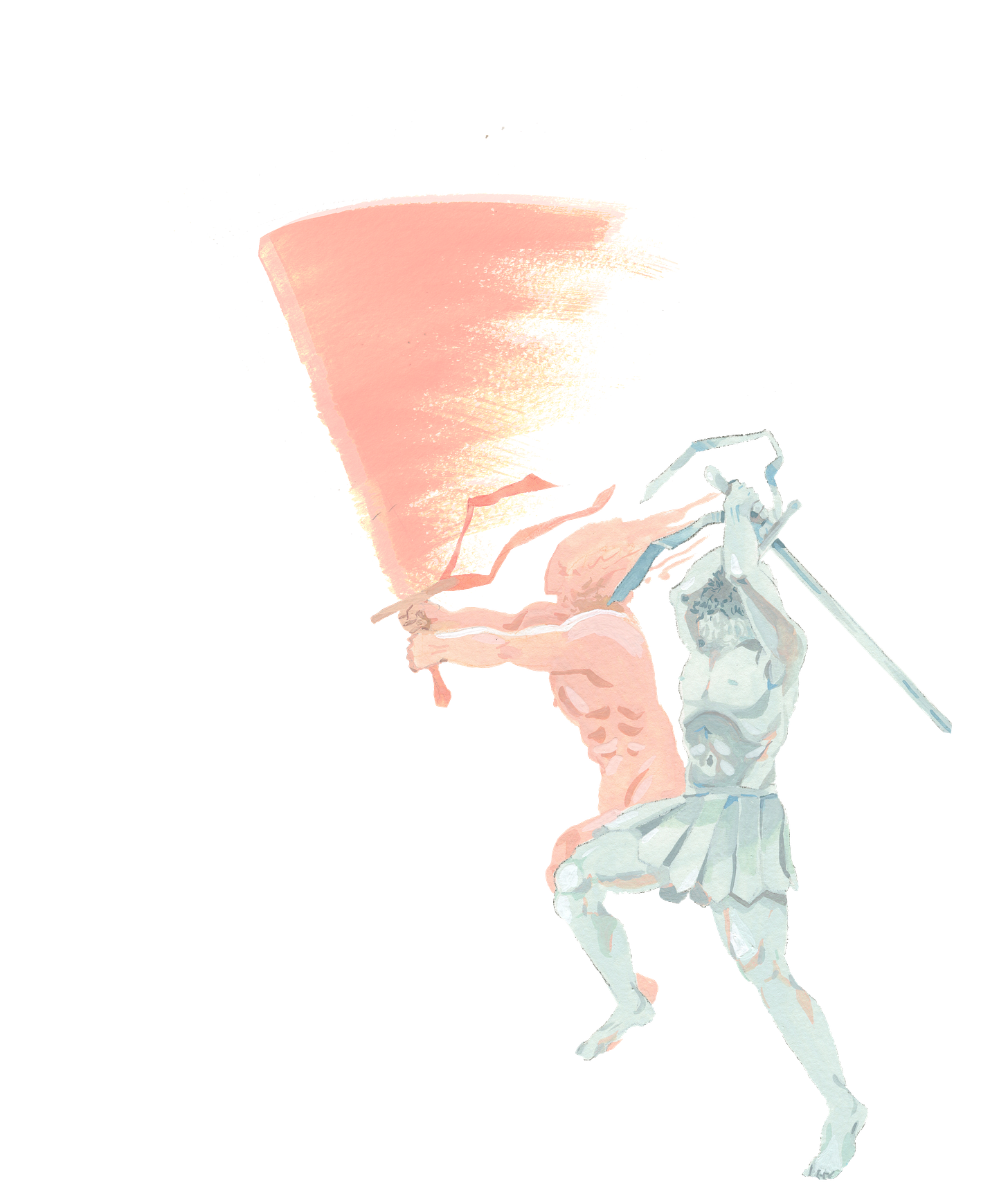

Take this asset for a painting I made for a upcoming print project called The Poison Garden. I knew what I was going to use it for as soon as I painted it.

Because I painted it with the image below in mind.

Heracles’ sword deserved to move with a furious and fiery swing! So, I paint a swish of pink fire. First idea, best idea. I whip up assets like this frequently, as textures or add-ons to edit into a piece later. Most of the time they end up in the trash after I scan it and edit it into the final piece, but for some reason, I wanted to keep this interesting little swipe of pink. I’ve been doing this more often this year, keeping little things “to paint on later”. Because so much of our best work comes free of context, conditions, or obligation, and because my painting practice has been stifled recently (mostly through my own inaction). And shortly after I drew a rare direct-to-paper drawing onto it. And produced the following image:

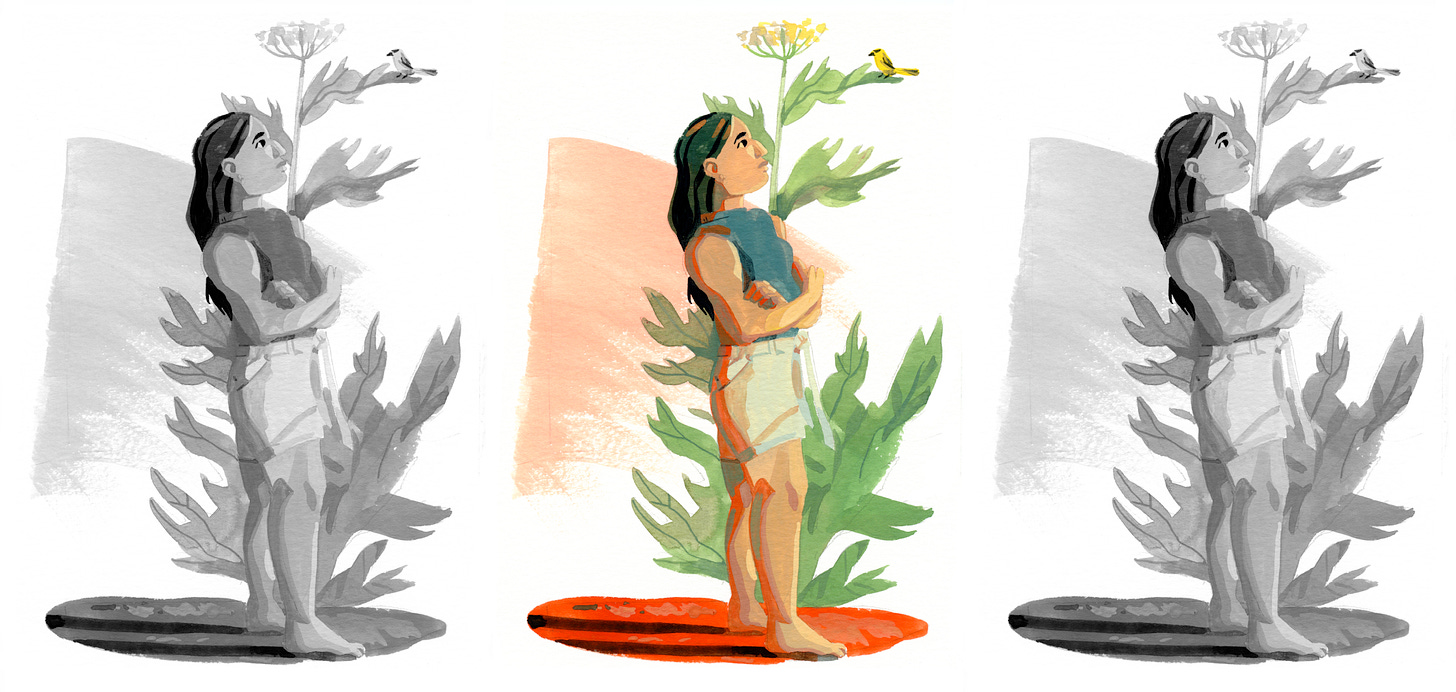

This is a character, Inoki, from the book MAK and I are developing called Red Clay Mountain. I am very proud of this little 4 by 6 inch painting. I’m especially proud of the color values that I was able to achieve from a pretty wide range of hues. I love to talk about how hues hold tone in deceptive ways, one day I may write a whole blog about paintings that do that well. In this painting though, that shows up mostly in the green (Heracleum) plant and red clay, as well as the shadow on her heels.

Earlier this year, something similar happened. A year ago, I painted this scene from a trip to Tennessee with my friends Zach and Cailin, where we stayed in a cabin for three days in the serenity of Appalachia. The painting was made sitting on the porch, listening to the creek run quietly. Nothing beats painting from life. It can be difficult but it’s very rewarding to try and match colors and shapes directly.

About six months later, I ordered some duralar— the same transparent sheets of plastic used for animation cel painting. I tried two different techniques using lines on the front layer of the duralar, and then painted the cel colors on the back. The draft on the left uses poster color for the lines, while the one on the right uses permanent marker.

After the duralar was dry, I was delighted! It looked so much like animation, and was exactly the vibe I was looking for for the comic; the only thing missing was a background. I looked around. The painting of the woods was strung up in my studio on a clothesline I keep full of recent work, and then a bit of magic happened.

WAPAOW! Fatimah and Willy playing in the woods. Red Clay Mountain feels a lot more real after doing little tests like these. Now I just gotta draw the (rest of the) damn thing! And paint it!

All in all, if your gut isn’t a pathological liar1, and you’re willing to follow it, you can end up with a ton of fun surprises in painting and drawing. Art doesn’t have to be a pressure cooker. You don’t have to make the perfect thing the first time you break the blankness of a page, and you don’t even necessarily have to “fix” the parts of it that are the most difficult for you. Sometimes finding a cheap workaround is what you actually need if it’s what it’ll take to keep you at the practice itself.

Perfect yields to done, I always say.

Until next time, substack!

If your gut is truly an unreliable narrator and you can’t figure out how to think your way out of that box, the cure may actually be acting first, balancing later. Sometimes just making something to prove the demon on your shoulder wrong can tip the scales.